After 25 years, Claire Parrish LG revisits a North Hertfordshire school and it’s remarkable artwork.

25 years ago, the charity Children in Need asked me to give a series of talks to secondary schools in North Hertfordshire. At the time, I’d given up any ideas of being an artist and was doing ‘proper’ work instead. So turning up at Barclay School in Stevenage, with my head full of what I hoped were useful facts and taking a last look at my lecture notes, I walked – almost literally – into the Family Group. When I’d recovered my notes, and from my surprise at seeing such an extraordinary bronze sculpture in front of a school, the waiting & amused Headteacher gave me a potted history of how they had been its proud owners since Henry Moore delivered it to them in 1950.

After the Second World War, Hertfordshire County Council embarked on a significant programme of building new schools, and part of the budget had been set aside to purchase artworks from leading British artists. Barclay school was to be the first purpose-built secondary school constructed anywhere in post-war Britain: Hertfordshire County Education Officer’s Report on School Building stated that the Barclay School ‘will in many ways be unique and it will not only be (a source) of local pride… there will be few, if any, other schools in England to compare with it’.

Designed by Brutalist architects Yorke, Rosenberg & Mardall, it was suggested that this flagship school should have a piece of sculpture ‘by the distinguished modern sculptor Henry Moore… whose work is generally recognized both in this country and abroad as being among the finest produced by any English living sculptor’. The County Council could not afford to buy a Henry Moore even in 1949, and anyway, there was some reluctance from Council members. But through private donations, half the cost was raised ‘and for Mr Moore to materially reduce his price because a copy of the work concerned can also be sold to the U.S.A… by this means the County Council will acquire a specially commissioned and designed piece of sculpture at approximately one-fifth of its actual value’.

Moore’s thoughts of using the family as a focus for his work had started well before the war, however: in the mid-1930s, Walter Gropius and Maxwell Fry had wanted Moore to design a major public sculpture for a progressive school in Impington, near Cambridge. This school was designed as a focal point for the entire community, for parents as well as children. But when war broke out, Cambridgeshire County Council could no longer afford Gropius’ full design, scaling back the project and cancelling the sculpture commission when Gropius emigrated to America. Despite this, Moore continued to develop the motif of mother, father and child (or children) through drawings and smaller-scale maquette compositions, while still exploring his ideas for reclining and internal/external figures. Moore used drawing to develop family group compositional-theme ideas, and as a way ‘of sorting them out’. Also, his home life was about to shift: in 1946, Moore and his wife, Irina, had their first and only child, and so the focus of the family group in Moore’s work took on fresh significance.

Finally, in 1947, it was John Newson, a friend of Moore’s and then Director of Education for Hertfordshire, who approached him with the proposal of a sculpture for Barclay School in Stevenage. Moore happily agreed: ‘for here was the chance of carrying through one of the ideas on a large scale which I had wanted to do. I went to see the school and chose from my previous ideas the one which I thought would be right for Stevenage and also one which I had wanted most to carry out on a life-size scale’. Moore was finally commissioned by Hertfordshire County Council in 1949, accepting a reduced fee of £750, which was just enough to cover the cost of his materials, casting and transport.

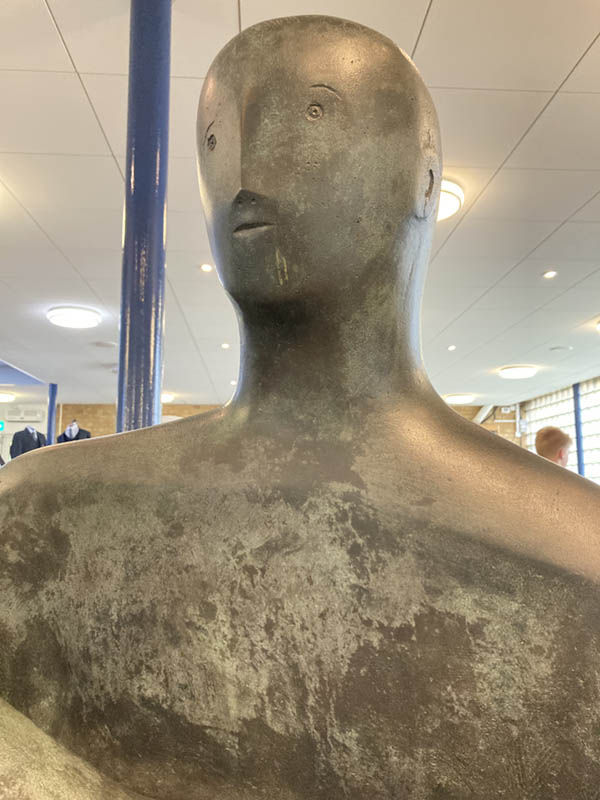

After choosing the maquette he wanted to enlarge for Barclay School, Moore made a plaster working model of the sculpture, which provided him with an opportunity to refine his design away from an earlier, more ‘modernist’ treatment of the male head. Moore explained, ‘in the small (earlier) version, the split head of the man gives a vitality and interest necessary to the composition, particularly as all three heads have only slight indications of features. When it came to the life-size version, the figures each became obviously human, and related to each other and the split head of the man became impossible, for it was so unlike the woman and the child.’ So the treatment of the man’s head became more sensitive and naturalistic, like the mother and child’s.

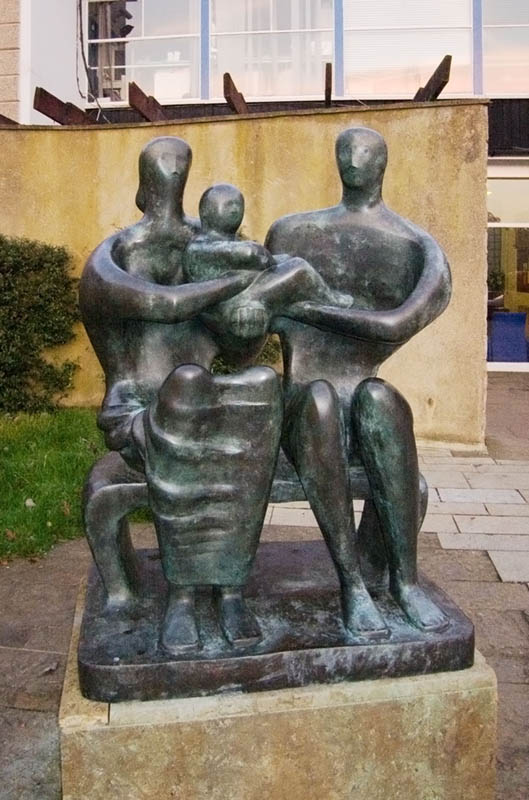

This revised maquette was now enlarged by Moore and Bernard Meadows, his studio assistant. Moore and Meadows constructed an armature, probably from wood or wire netting, and built up layers of plaster. Then, in three parts, the mother, the father, and the adults’ arms holding the child were made and assembled together, so that the surface texture of the sculpture and the individual features of the figures could finally be worked on. This plaster is now recognised as the earliest life-sized sculpture Moore made.

The Family Group bronze for Barclay School was cast at the Fiorini Art Bronze Foundry in London, using the lost wax process to cast sections of the work which were then assembled. Working with Fiorini wasn’t straightforward, and looking back in 1951, Moore said he felt that ‘the group was really too big for them to handle and they had lots of difficulties, in fact they took a whole year to do it, with a great deal of worry over it to me’. Consequently, Moore decided that the next two casts should be made by Fonderie Rudier, Paris, who had cast many bronzes for Rodin: these next two casts were made differently using the sand casting technique in at least ten sections, which were then reassembled and secured together with pins.

Moore had always intended for the Barclay sculpture to be displayed outdoors, so chose the stone plinth and a curved curtain wall behind it, directly outside the entrance to the school. It was quietly installed in 1950.

The following day, the local postman delivering the post described himself as ‘shocked’ when he first saw the sculpture: ‘I looked and almost let the letters I was carrying drop from my hands … They tell me it needs a lot of appreciation – I bet it does’. In an article titled ‘‘Belsen’ Statue Came in the Night’ the Daily Dispatch records local reaction as a mixture of negativity, confusion and anger, as people weren’t consulted or warned about the sculpture’s arrival. It was described as ‘unreal’, ‘ugly’ and ‘not art’; there were even fears that rotten eggs might be thrown at it during the unveiling ceremony. (A similar comparison to looking like something from Belsen was also made to Moore’s Reclining Figure: Festival, exhibited at the Festival of Britain in 1951.) Conservative commentators also joined in. Responding later to Moore’s Family Group in 1950, the painter Sir Alfred Munnings said: ‘Distorted figures and knobs instead of heads get a man talked about these foolish days. Anyone can do round balls for heads. Few can chisel the features of a face.’ When asked in an interview who was to be the judge of what constituted good art, Munnings replied, ‘the man in the street.’

Barclay School’s headmaster, however, was recorded as liking the work, noting how students enjoyed walking up to it and touching it.

In 1975, Moore wrote to Evelyn S. Ringold, that by the time the full-size bronze was cast, his daughter Mary was two years old, and that his family life was ‘very happy indeed. Perhaps the family groups reflect this outlook. I don’t think I had any philosophy of English Family life or American family life in mind, though doubt my own childhood would have an influence. I was the seventh child of a family of eight, my childhood was very full and very happy.’

The Family Group remained outside the school for sixty years, and in 1993, Barclay School became a Grade II listed building. Then in 2010, school staff stumbled across months-old CCTV film showing an unsuccessful attempt to steal the sculpture. Weighing in at 500kg, and sadly, fears of future theft to sell on for scrap metal, risks of vandalism, and the cost of insuring against its escalated value, left the school with no option but to move it into their main reception area indoors.

Recently, when I called to make my appointment to re-visit and photograph the Family Group, the receptionist warned me that the sculpture would be covered in school-leavers ties as was school tradition on the last day of term. Was that OK? Well, its quite a tricky question to answer

on the hoof, weighing-up its eye-popping value – currently £20,000,000 – its international artistic and historic significance, my own (I accept pretty limited) ideas of how and where sculpture is to be seen (but includes being at arms-length/rope barriers/air controlled galleries/laser security, forensic plans about future preservation, conservation etc.) balanced against asking why shouldn’t every school have a real, tactile, relationship with wonderful original sculpture, that plays a part in the rituals of their school’s year?

Even so, walking up to Barclay, it was a sad moment to see the empty plinth and redundant curtain wall outside the school: few critics, museum directors, collectors and surely not Moore, could have guessed the meteoric transformation of his international reputation or anticipated the elevated prices his work would achieve on the world art market. I sensed that he would’ve been ok with the end-of-term ties, but less easy with the compromises that monetary value brings.

And now finally, to seeing The Family Group facing me as I walk into reception, (what’s this – no ties?). It could not be sited in a busier part of the school: students stream by, lean bags against the plinth, the end of day bells peal, the cleaners start to pull buffing machines out of a cupboard, parents queue, all is a buzz around this sculpture. I take 5 minutes to get up close and scrutinise. Spotting a strip of Sellotape stuck on the mother’s leg (evidence of the earlier tie decoration) without thinking, I carefully peel it off. My shock was followed by confusion, I have touched this fantastic Henry Moore bronze, but no alarms are going off, no one seems to be about to arrest me. The receptionist reassures. So off I go around the back, and find a small split in the bronze seat now visible – historical evidence of the bungled heist – revealing slithers of original plaster under the metal skin. Ten more minutes of staring at the figure’s feet, hands, faces, eyes, the jolly bouncing baby, the parents’ smiling confident faces looking forwards: and the little flicks, scratches, marks of daily life, the patina from seventy-two years of living with teenagers.

Standing back, looking at the three figures, the arms of the mother, father and child linking together, the parents mirroring each other in response to the child. Moore said ‘the arms of the mother and the father (intertwine) with the child forming a knot between them, tying the three into a family unity’ (1.) It is a tender work: protective and stable, a symbol of hope, pride, love and care. What a thing to be around every day of your school life.

Claire Parrish LG, 2022

Family Group (LH 269) is sited at Barclay School, Stevenage, Hertfordshire. Henry Moore was a member of The London Group between 1930 and the late 1940s.