Play is becoming a big thing in Art. Tim Pickup from Genetic Moo LG discusses why this is a good thing.

Play is becoming a big thing in art.

In 2019, TeamLab’s exhibition Borderless with its ‘mesmerising interactive art installations’ took the Guinness World Record for the world’s most visited museum, beating the Van Gogh and Picasso museums. You’ve probably seen their work online, huge projected spaces filled with brightly coloured animations of trees and plants gently responding to an enchanted audience. Also in 2019 the V&A held a one day conference called Future Museums: Play & Design. Here is their introduction :

Play is a mode of creative problem-solving, imagination and experimentation that helps us understand how we can impact the world and affect change. How can cultural institutions become seriously play-filled spaces? How can we activate collections, design spaces and programme content that will empower our audiences through the power of play across generations and in a fast-changing and uncertain world?

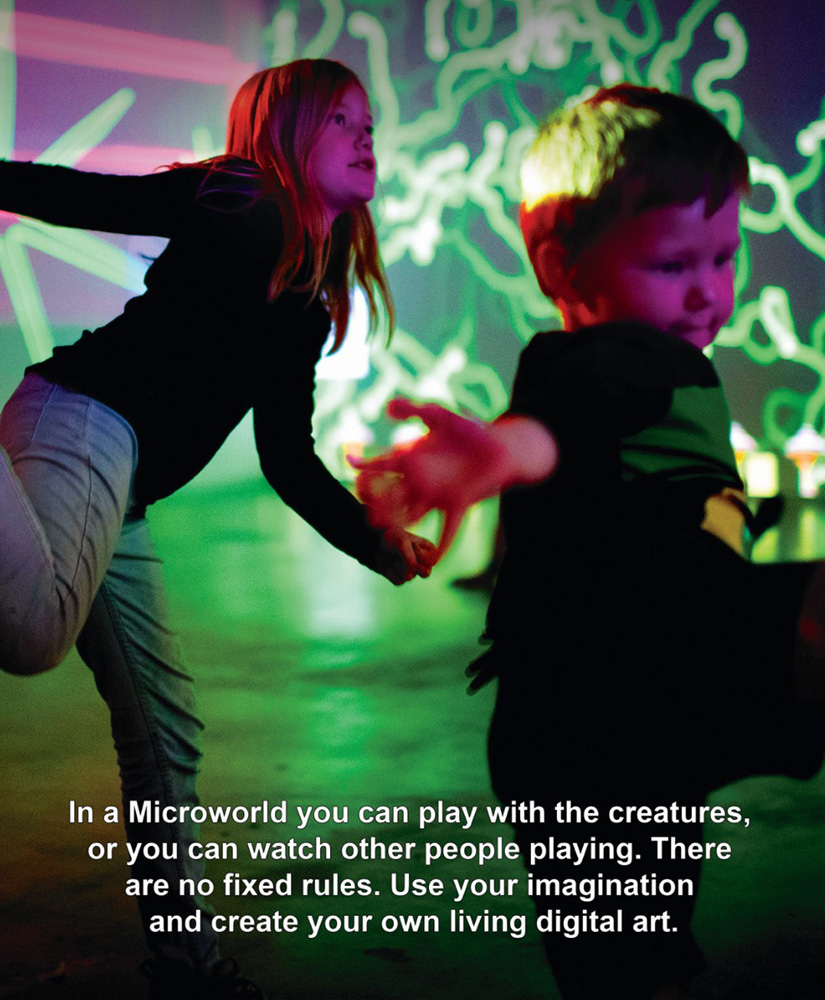

The first session that day was titled Why is Play so Important? And that is what I want to explore here. I want to explain why encouraging people to play is important to me as part of an art group called Genetic Moo who make large-scale interactive spaces which we call Microworlds. I’m also going to try and explain why play isn’t “just for kids”.

We make all our interactive art using computer programs and sensors. One of the first computer magazines BYTE launched in 1975. On the cover it said “ Computers – The world’s greatest toy! “ and this is still the way I think about computers today. Each day I play with this toy trying to create weird and wonderful things including art. So making the art itself is a type of play. You tell the computer to do something, it does something else, you iterate back and forth, trying things out, improvising, randomising, hacking and playing. Now I’m in a collaborative digital art group with my partner. We also play together (which you can read about in more detail in Sandra Crisps Process essay). We try one thing after another until something sticks. A playful process. Getting other people to play with our art seems a natural extension of this process. We play – let them play too.

But why do humans play? Founder of the National Institute for Play, Stuart Brown describes play as “preconscious and preverbal – it arises out of ancient biological structures that existed before our consciousness or our ability to speak”, the idea being that play prepares animals for a world which continuously presents new challenges. When playing we can try out some ‘made up possibilities’ and learn new skills and tactics without being directly at risk from real life. Brian Eno considers play as a precursor to art:

“We all know that children learn through playing. Everybody understands that when kids are doing things like tipping liquid out of cups and playing with stones and building things and singing songs and so on …. we know that that’s all part of their way of coming to understand the world. Nobody says ‘why are those children wasting their time doing that? Why don’t they do something useful?’ You know that that’s what children have to do. That’s their way of becoming acquainted with reality. Children learn through play ….. and adults play through art”.

So where does play fit within our art? If a painter uses paint and a sculptor might use clay, what is our medium? We used to say it was pixels – as our art is displayed digitally on monitors and projections. Then we’d say our medium is computer code as that is what runs our art. But over the years we have come to realise that as interactive artists our real medium is interaction. What do we allow the user to do? (We call them users because they are using a system which they can change to an extent – they are doing more than just viewing). How do we construct a piece that allows the user to explore what happens next? Play is central to how humans discover the world and the construction of playful possibility is central to our art. Because everyone knows how to play we can say that our art is for everyone.

When experiencing a traditional piece of art in a Gallery a large part of the experience is based on how good your knowledge of art history is. With interactive art you don’t need that, in fact, it gets in the way, you are in the interaction and your experience is as direct as if you were in a living space which responds to you as you respond to it. Less thinking, more doing – and a large part of this doing is playing. Which is also why kids respond so well to interactive art – they don’t need to be told what to do, they don’t want to be told what to do – they figure it out for themselves. They play. And when they play they are using their agency. The ability to act.

When we make art we are designing a system in which the user can play with their agency.

Over the years we have noticed some adults find the notion of agency and play in art difficult, perhaps embarrassing – “the art should be doing the work not me”. It reminds us of one of our favourite sea creatures, the Sea Squirt. It has a telling life cycle. When young it swims around exploring its world, moving towards nutrients and away from harm, learning and growing. Once it becomes an adult it attaches itself permanently to a rock and its life enters a purely passive phase. From now on it filter feeds and even digests its own brain – it doesn’t need it any more.

Play has been a part of modern Art History from the start with Duchamp and his Bicycle Wheel and Rotoreliefs through Dada, Fluxus, Participatory Art, Happenings, Art Games, Web and Interactive Art – but always somewhat on the periphery. Roy Ascot who made a series of Activity Map art games as part of his reinvention of the Art School in the 60s encouraged his students to “Stop thinking about artworks as objects, and start thinking about them as triggers for experiences”. But if art is a trigger for experiences then where does the art gallery fit in? The Gallery model based on promoting and building art careers and then taking a certain percentage of the sales is being superseded. Take for example the ever-expanding empire of Japanese art collective TeamLab, mentioned earlier. They have sidestepped the traditional art world by building their own mega museums filled with playful art catering to a digital generation eager and willing to pay for immersive environments and large-scale participatory events. And these are the shows that are breaking records. Their audience has been playing video games all their lives, and this audience effortlessly brings their playful expectations into physical arenas where they can act together.

Because our art medium is agency we draw inspiration not from the art world, but from a medium where people build an endless variety of systems which allow people to explore agency together: Tabletop Board Games. Reiner Knizia is a prolific game designer (over 600 and counting) and is considered the Mozart of Game Design, revered for the astonishing elegance of his work. Some of the most beautiful Knizia designs consist of a handful of rules that give rise to complex and subtle play. One of our favourite games by Knizia is called Modern Art where you play a modern art dealer, auctioning paintings from hot new artists. The rules generate a wildly fluctuating market with evaluations going up and down season by season. Each action you take affects all the other players and all future market transactions. You have to ride this chaos to win the game.

Players’ actions create half-seen ripples of cause and effect. The way the game manipulates players’ agency becomes an aesthetic thing in itself. This orchestration of agency to make a game appear as if from nowhere is what makes Knizia a genius in this field. He has said that the central tool in his game-design arsenal is the scoring system. The thing the players’ actions are leading towards, and here there is a crucial difference between board game design and interactive art. Interactive art is also about manipulating agency but there is no end goal in particular. We use the term ‘open play’ to describe our art. That is the same as play but without a fixed set of rules or victory conditions.

The end goal is engaging people within a museum or gallery context. So we consider things like have the audience had a meaningful interaction with the work. Did they understand what they were doing? Did it give them a sense of agency? Did they enjoy exploring their agency? Did they discover something new? Did the artwork give them the chance to play with the world? If the answer to these questions is yes then we have made a good piece of interactive art and if they engage for a considerable length of time (several minutes to an hour) then we know we’ve made a great piece of interactive art and have shared the power of play. In a world beyond our control, giving people back some agency is a good thing that art can do.

Tim Pickup, Genetic Moo LG, 2023

– Worlds Unbound – The Art of TeamLab by Laura Lee

– Play by Stuart Brown M.D.

– Brian Eno in conversation with Adam Buxton from the podcast Play & Art

– Games – Agency as Art by C.Thi Nguyen