“When I started my inquiry into the links between Health Care and Art I didn’t realize that it would take me on a beautiful journey into people’s lives.” Marenka Gabeler LG

I consider myself mostly a painter. And I am not naturally a writer. I identify with working through questions visually, exploring that which is not formed by words. But both writer and painter are in some ways storytellers, so I take up my pen and look for the common ground. Let’s see where it takes me.

My interest in the cross over between art and health started with my grandmother, some years ago. She suffered from Alzheimer’s and at the time I was trying to find ways to connect to her. We made an illustrated book of a childhood memory she was then still able to recall- of walking to school as a young child through vast Dutch fields. I helped draw her childhood home, inside as well as outside. We even drove around the countryside to try and find it, if it still existed.

My other, Indonesian, grandmother, had been ‘laid out’ at home after she passed away. This, perhaps a Dutch-Indonesian tradition, was made possible by a fridge underneath her bed that slowed down the body’s decaying processes. It gave me a chance to draw her on her deathbed, be it in the freezing cold.

Encouraged by the desire to help, I started facilitating art workshops with patients in hospitals. I even made “visual” art with blind people (clay amulets imprinted with leaves and flowers), something I had never imagined. What inspired me was when I saw people’s moods lift and their faces light up when they immersed themselves in creative activities.

So I ask, what are the different possible ways that Art and Health Care might connect, cross over, or feed back into another? I interviewed London Group members, whose lives and practices relate to the topic, to find out.

Interview #1:

Julie’s story – Death As A Thread Through Life

I didn’t realize but Julie is someone with a rich family history. It was a sunny day and Julie was the first person I telephoned. I can’t remember conducting an interview ever before so I didn’t quite know what to expect. But Julie was a big encouragement. Hers was a warm and kind voice on the other side of the line. We felt an instant connection.

Her parents had been children from Nazi Germany. They arrived as refugees in England during WWII. Her father had even managed to help some children get on to the Kinder-transport.

Her mother, whose family died in the war, was an incredibly joyful woman who, at times, would go into deep depressions, ‘like a fog that came over her.’ Julie says, ‘The presence of death in your family makes you more aware of the politics of war and death and teaches you to actually enjoy painting’.

When she was small her parents took her to see an Edvard Munch exhibition at the Hayward gallery. Julie felt compelled to see the paintings. Looking at Munch’s emotional expressions, it struck her that through painting you could make emotions public so you didn’t have to feel alone.

‘I’m going to tell people my emotions!’ she thought. Later she realized that painting is not telling people the emotions but it’s more like conveying the essence of something.

Her parents retained their German identity throughout their lives. Julie realized that other people’s homes were different and it set her apart. It made her aware of her background. The home would smell of German cooking and she would always hear the comforting sound of her father’s voice, having intellectual conversation on German thinkers. Her mother would call out, ‘No Freud at the dinner table!’

Her mother suffered a long struggle with Multiple Sclerosis and Leukemia. The onset started when Julie was 12 and after a long illness, her mother died when Julie was 18. This had a big impact on her life and explains how she ‘internalized the presence of death’- it had made her much too aware of death at a young age. Then, when Julie developed an auto-immune lung disease in her early 20s, she was hospitalized, making her, again, aware of the preciousness of good health. Luckily the disease disappeared over time.

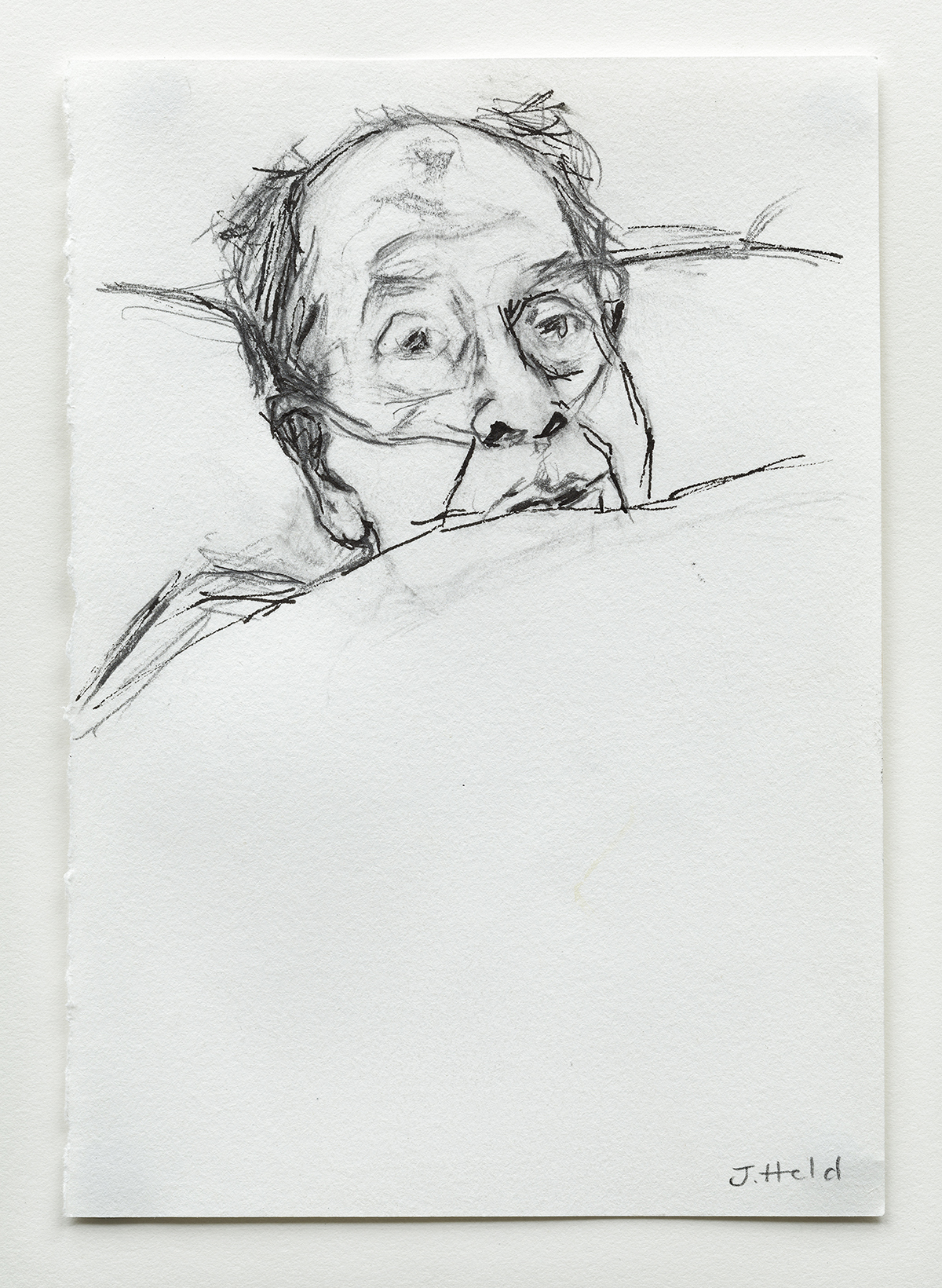

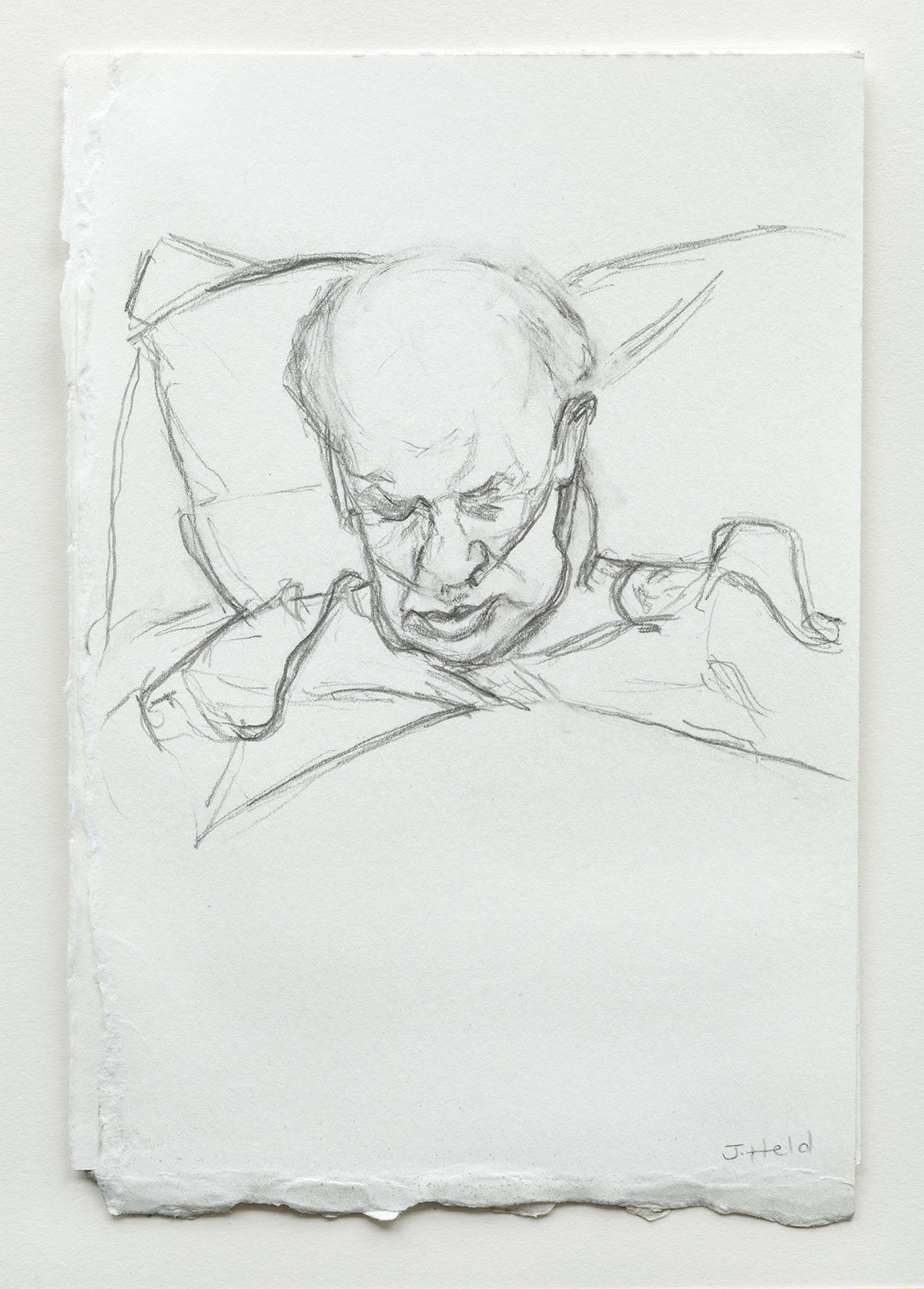

Both Julie’s father and brother died recently. Her father’s death had been an easier death to take than her brother’s, who had been in his prime. Julie spent a lot of time with her father in hospital. He had been her friend as well as a father. By drawing him she drew a celebration of life, expressing the love for her father and their relationship. They were good moments she spent with him, those last days. Drawing had been a good way to come to terms with his death.

I look at a series of pencil portrait drawings of an old man. It is a man on his deathbed, Julie’s father, Peter. Some of the lines are short and strong, some drawn with pen, as to emphasize a physical presence. Other lines are long, with grey pencil, they seem almost caresses to me. In one of the drawings the area of one eye has been rendered lightly, or perhaps rubbed out a bit. More faded, they open up a sense of vulnerability.

I ask if she also drew her father after he passed away, thinking of my grand mother’s death drawings, but she hadn’t. She had made death drawings of her mother. This had been after Julie finished psychotherapy. Because her mother had died in such a developmental part of Julie’s life, she sees art making as a form of therapy. ‘Painting helps to gain self-knowledge, of how others impact on you and you on them. You become a better listener.’

One of them, “Swimmers in Wengen”, shows children around a swimming pool, and is based on a childhood memory of a holiday. Painted in oils, the strong blues and defined lines I find reminiscent of German expressionist painting.

Julie draws upon this memory to explore Thomas Mann’s novel ‘The Magic Mountain’, after she had been in hospital for 6 weeks following the diagnosis of lung disease. In the novel a young man who goes to Davos to visit a cousin, but ends up ill, staying for 7 years.

On one level, the Magic Mountain is about disease, ‘not merely of individuals, but also of a whole age. Where disease appears as the prerequisite of spiritual growth, Mann plays his favourite theme of the polarity between spirit and life; the transcendence of this polarity in the name of humanism is central to the novel’. 1

I questioned Julie about what type of art, she feels, is suited for hospital walls. Should it be gentle and easy to look at? Or can it also be more intellectually challenging?

‘It could be both’, Julie feels. Just easy for the eye would be patronizing, she finds. It would bring ‘no “interruption” to the wall and its near space. People like more difficult work, as this can result in chatting and this brings people together either in consenting views or not. Good work that needs looking at and looking with brings contemplation away from the body, which is the very thing that brings patients into hospital.’ Julie talks specifically about risks that can be taken for works that hang in corridors, the more neutral spaces, not in wards. She states the positive role of paintings on a hospital wall: to cheer up the hospital environment, making it a more normal one, to have pictures and colour around.

‘Munch, whose personal tragedies, sicknesses and failures fed his creative work, once wrote “My fear of life is necessary to me, as is my illness. Without anxiety and illness, I am a ship without a rudder…. My sufferings are part of my self and my art. They are indistinguishable from me, and their destruction would destroy my art.” 2

I would say that Julie takes after her inspiration. But instead of suffering turned into anxiety, Julie’s experiences have encouraged a love for life that energizes her art.

Marenka Gabeler LG, Nov 2020

I want to thank London Group members Julie Held, Bryan Benge, Judith Jones, Victoria Rance, Susan Wilson, Eric Fong and Suzan Swale for letting me interview them to inform this topic. This is an ongoing project. I continue my investigation and aim to include interviews with the other members I spoke to in subsequent articles. See below for further articles.

1 cliffsnotes.com The Magic Mountain

2 Lubow, Arthur. ‘Edvard Munch beyond the scream’, SMITHSONIAN MAGAZINE, MARCH 2006.

Art and Health, A Story

Interview 2 Bryan Benge LG – The Art Of Caring

Interview 3 Victoria Rance LG – The Art Of Hope