James Faure Walker LG reflects on his 1978 Artscribe article which challenges a campaign against contemporary art and, in the process, illuminates how artists have responded to the changing climates of art criticism.

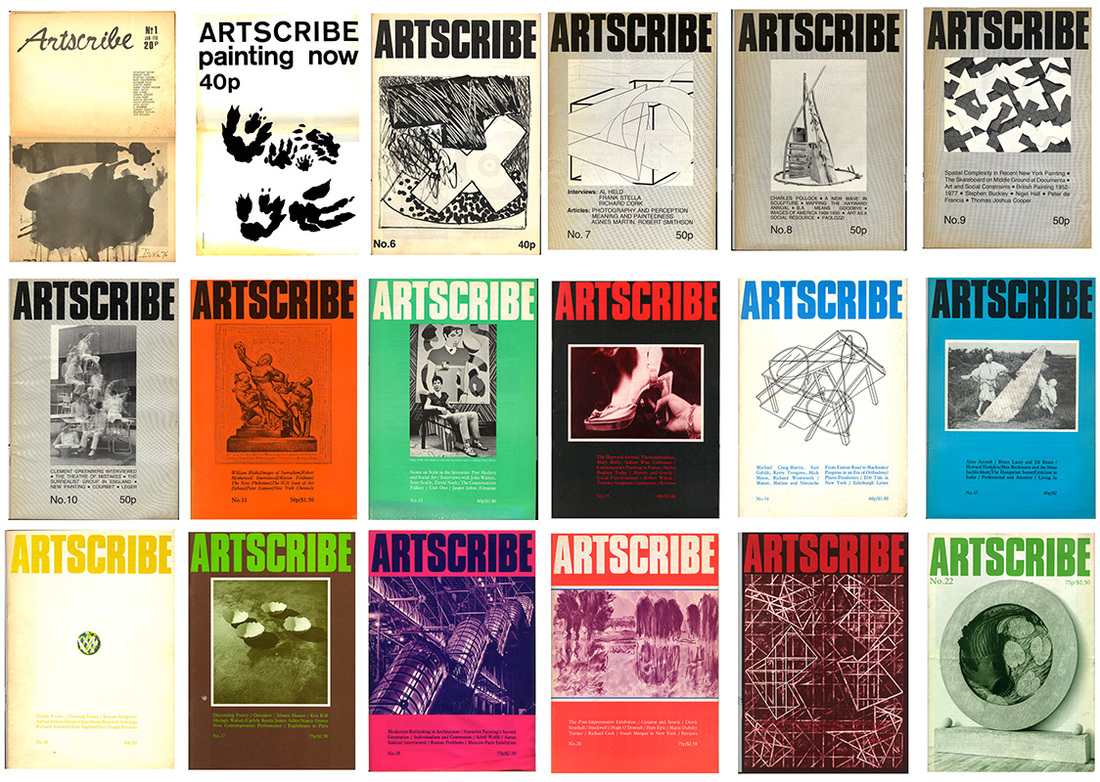

Recently I re-read an essay I wrote forty years ago – ‘The Claims of Social Art and Other Perplexities’ published in Artscribe magazine, an artist-run magazine founded in 1976*. I was the editor. It was in response to a campaign against contemporary art; some of it coming from freshly arrived critics and curators. These had switched from championing ‘New Art’ to campaigning for an ‘art for ordinary people’: social realism, uplifting murals, banners, community projects. No more abstract art, no more elitism, no more inaccessible art. The audience, they said, was tiny and vanishing fast. ‘Modernism’ was finished.

Why did I bother to write a response? Today most of us know they got it pretty wrong. The Tate Modern is bursting, the Royal Academy had a run of provocative and sell-out shows – the New Spirit of 1981, Sensation of 1997 – and whatever you may think of the Frieze Art Fair and the booming art market, you can’t say the public has walked away. Yes, here and there social realism turns up, but as retro chic.

Back then the hostility was real. It blew in from both the left and the right. The critic, Peter Fuller, initially a disciple of John Berger, had a keen following. It isn’t difficult to rubbish new art, and indignation was his forte. The BBC, where contemporary art never got a mention before midnight, gave prime time to ‘Phart Art’, with Fyfe Robertson ridiculing the ‘way-out’ art at the 1977 Hayward Annual. The year before Carl Andre’s bricks at the Tate had been treated as a joke by the tabloids, and only weakly defended. The Times had Hockney and Kitaj posing naked, claiming that art schools were suppressing life drawing. The Serpentine hosted ‘Art for Whom?’ (where Richard Cork rejected the open submission, replacing it with his stable of social artists). The Whitechapel put on ‘Art for Society’.

There had been a change of atmosphere, disillusionment with the optimistic art of the sixties, and among artists, a more than usual contempt for critics. The grievances, the divisions, were mixed up. Who were the progressives, who were the radicals, and who were the conservatives? Was conceptual art, deliberately impenetrable, the avant-garde? That had been the line of Studio International under its new editor (also Richard Cork) until this change of direction. Did it mean that painting in general was ‘over’, or was it only American-influenced abstract painting? Allegedly, that was empty of ‘Meaning’. It was ‘formalism’, a truly dirty trait, and probably counter- revolutionary too.

I am writing this note because in that essay I reproduced a painting by David Redfern of a factory, which was in that Whitechapel show. I did not comment much on the painting then, or on realism in general. Buried amongst all the posturing and not so wonderful artworks parading their social consciences were a few straightforward, and decent, realist painters. Contrary to all the stirred up antagonisms, most ‘abstract’ painters lived happily alongside figurative painters.

The influence of critics and magazines today is negligible. It is all social media now, and young artists would not take to being hectored through a megaphone. Fuller used to demand that artists ‘take their standards from the future’, and whatever you took that to mean there were earnest heads nodding away. In 1978 the slogans hit home. The State of British Art conference at the ICA about the ‘crisis’ was absolutely packed. ‘Modernism’ was in the dock. I was called in at the last minute – possibly John Hoyland had dropped out – to speak on a panel. I was told I was representing ‘modernist formalism’. I was starting out as the loser-in-waiting with a bloodthirsty audience, and nowhere to hide.

That eruption of radicalism – or upmarket philistinism, call it what you will – lasted two years. Then the social guilt wilted away, or became uncool. The gossip turned to the champagne fountain at Schnabel’s opening at the Mary Boone Gallery in New York. It was ‘post-modernism’. The alliance of born-again figuration and watered- down Marxism fell apart. Some on ‘the left’ re-emerged on ‘the right’. Prince Charles lambasted modern architecture in Peter Fuller’s new glossy, ‘Modern Painters’. Denim gave way to tweed.

In our magazine we knew we had to cope with a pluralist art world and covered whatever we could, and were not afraid to be critical. (I could see the shortcomings of abstract painting in Britain. I knew where it was provincial, mannered, and dogmatic.) You could not afford to be partisan. We had already published essays on post-modernism. What had frustrated painters, of every persuasion in the seventies was the lack of intelligent coverage. Studio magazine had a long history, and had till then been a well-regarded journal, but now it lost its way, and its readership.

What was this convulsion really about? Probably, about who controls the agenda. Some well-meaning critics set out to be engaged, and encouraged ‘art for the people’. In the process they alienated more artists than they converted. It got them noticed, but most were already speaking from a position of privilege. It was difficult ground. Hadn’t they read Hitler’s speeches on degenerate art? Or thought about Shostakovich? Their politics could be juvenile – phrases like ‘the capitalist option’ – and the art they promoted was largely awful. It elbowed what was good out of sight. I recall a meeting chaired by the great Richard Hoggart at Goldsmiths, when Michael Compton of the Tate turned to Richard Cork, and said with some surprise, ‘so you see the critic’s role as telling artists what to do?’

In retrospect it is strange that another story never had much of an airing. This had grown from the counter-culture of the sixties, from the vitality of the art schools of the time, from the confidence of young artists, from their lack of deference towards their would-be overseers. It was the idea that artists could manage their own destiny. Artists had organised studio provision, housing, and their own galleries, with SPACE and ACME. If critics were out of touch, artists could set up their own magazines – and their own exhibitions, as had happened with Situation, and was soon to happen with the YBAs.

It showed that ‘support’ for contemporary art was fragile. There were always those on the sidelines – not necessarily in the name of ‘tradition’ – ready to step in with their dreadful small minds. It showed how easy it is to discredit an artist’s oeuvre, to dismiss whole swathes of art as ‘playing with paint’, as meaningless, subjective, as merely aesthetic. Some careers were permanently damaged, just as the Prince Charles effect suppressed architectural innovation. The conceptual art movement had its sparks of brilliance, but it also had a deadening academic effect – as the late Freddie Gore once pointed out in an encounter with Joseph Kosuth at St Martins. It devalued imagination and elevated the factual, it worshipped the document, the proof, the text, typed and cleanly framed. It opened the way for the art theorist, for the artist’s statement, and for the art school with a hot desk instead of a studio.

I expect the controversies marked David Redfern in some ways. They left me wary of those who preach and are full of self-righteous certainty. They don’t even bother to look. (I hope I am not in that category.) I have more time for ditherers like Bonnard. Making paintings come alive is extraordinarily difficult at the best of times.

James Faure Walker LG, 2018

* Read ‘The Claims of Social Art and Other Perplexities’, Artscribe 12 (1978)